Facing Our Past, Changing Our Future, Part II: Five Decades of Desegregation in SFUSD (1971-today) Link to this section

“Not everything that is faced can be changed, but nothing can be changed until it is faced.” - James Baldwin

This is the second of a two part series on the history of SFUSD’s student assignment plans. Part I spans the early days of public schools in San Francisco, from 1851 to 1971. Part II covers our more recent history, from 1971 to the present day.

Part I of this blog covered the long period of legal and de facto segregation in SFUSD from 1851 up to 1971, the year of our first desegregation program. This installment covers the most recent fifty years, when SFUSD has increasingly made good faith attempts to desegregate our schools, achieving some success — but unfortunately unable to sustain it for very long.

This commitment, in addition to the policy goals of proximity and predictability, is why we are in the process of redesigning our student assignment plan. We hope that we can learn from both the successes and failures of our more recent student assignment history so SFUSD and the greater San Francisco community can work together to co-create the best, most racially just student assignment plan possible.

The Horseshoe Plan/Operation Integrate (1971–1978)

The Plan

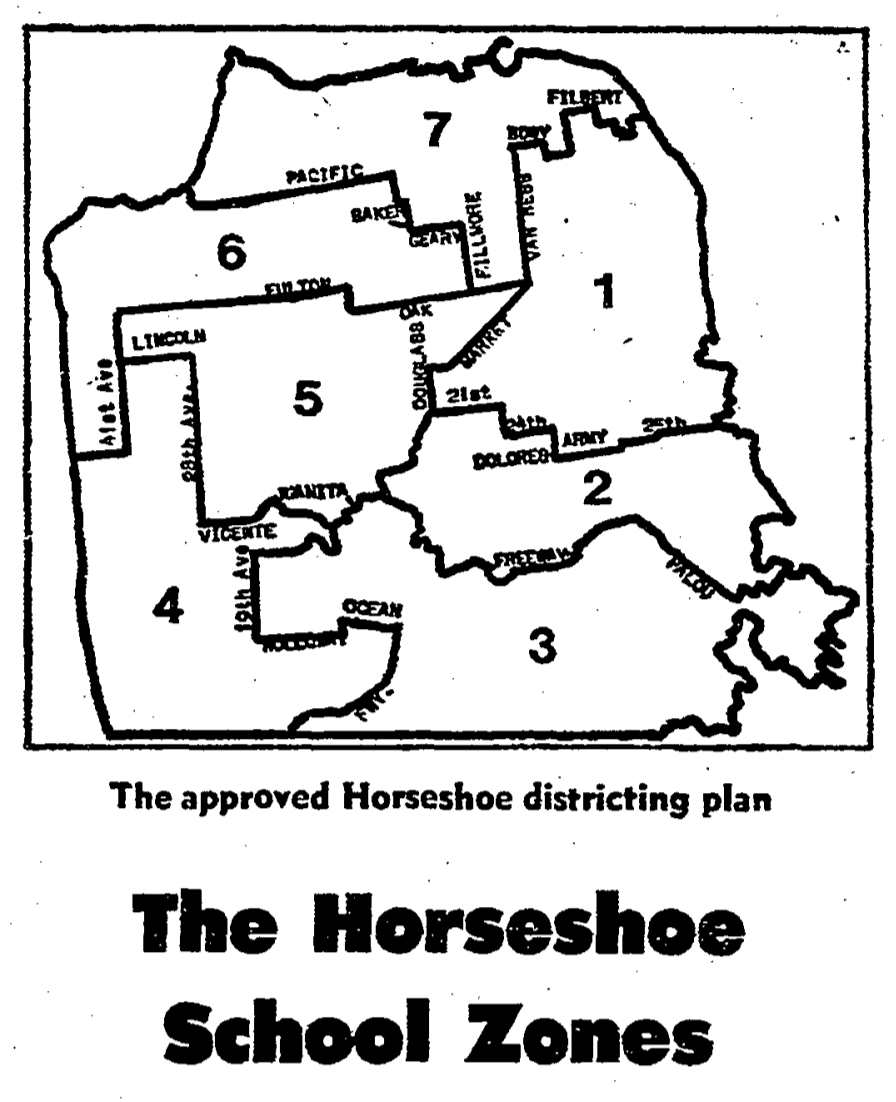

In 1971, SFUSD adopted its very first elementary school desegregation plan — called the “Horseshoe Plan” because of its shape on the map — which divided the city into seven contiguous zones. Students were assigned to schools within their zones in a way that created “racial balance” — which meant that each school’s racial demographics were roughly the same as the overall district’s. In 1974, “Operation Integrate” expanded the Horseshoe Plan to middle and high schools in SFUSD.

To achieve this racial balance, SFUSD implemented a busing program to overcome the segregation of San Francisco’s neighborhoods. According to the judge overseeing San Francisco’s desegregation plan, busing was the only way to achieve integrated schools in a segregated city like San Francisco. The plan called for students to spend half of their elementary school years walking to a school close to home, and the other half busing to a different campus within their zone.

Around this time, Chinese-American San Francisco families organized against English-only schools, winning the right to bilingual public education in the United States Supreme Court case Lau v. Nichols, which established bilingual education as a civil right for students across the country. The Horseshoe Plan accommodated the need for appropriate language settings by allowing families to apply for a “Temporary Attendance Permit” (TAP), an alternative enrollment process that allowed families to request assignment to the school of their choice.

The Results

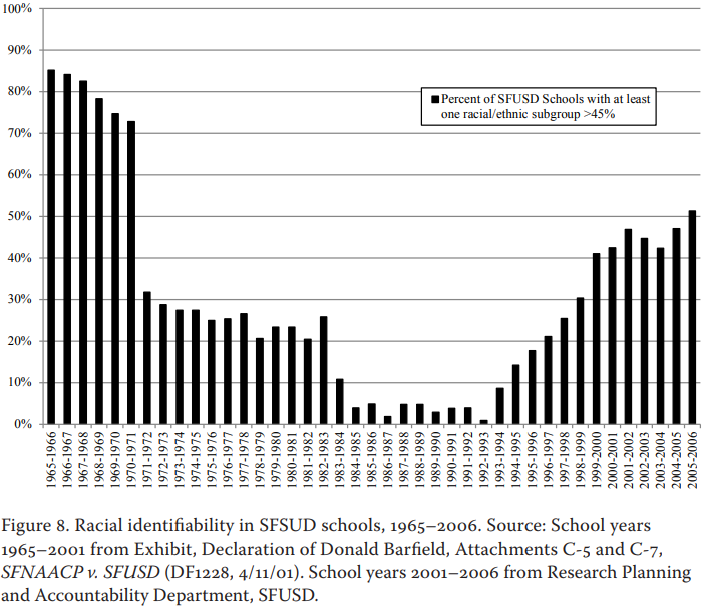

The Horseshoe Plan and Operation Integrate worked initially, especially at reducing Black-white segregation: by 1976, there were zero highly segregated Black or white schools. Asian and Latinx segregation persisted however, primarily due to the growth of Spanish and Chinese language programs, as well as the relatively small, dense geographic concentration of Asian and Latinx students in Chinatown and the Mission.

According to opinion polls at the time, families of all racial groups disliked busing as a desegregation strategy, but white and Asian families were the least supportive of SFUSD’s overall desegregation goal. These communities largely (though not uniformly) fought for access to neighborhood schools.

Though it was originally designed to accommodate legitimate “just cause” requests, like assignment at the same school as an older sibling or assignment at a school with the necessary bilingual education program, TAP was also frequently used as a loophole to avoid participating in the citywide desegregation plan. By 1977, ⅓ of all SFUSD students used TAP to attend a school other than the school they were assigned to by the desegregation plan; at the same time, schools were beginning to resegregate.

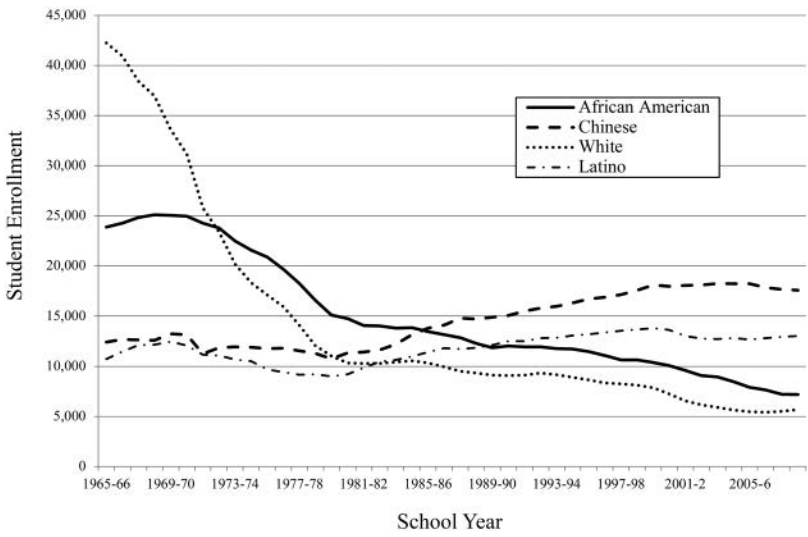

White (and, to a lesser degree, Chinese) flight also hurt the Horseshoe Plan’s efficacy at reducing segregation. SFUSD’s white student population decreased by 11% in the first year of the Horseshoe Plan and continued to drop precipitously over the next decade; Chinese student enrollment also decreased by 8% in the first year of the plan, but leveled off in following years. White flight in San Francisco was among the worst in the country — more than 20,000 white students left SFUSD following the implementation of Horseshoe — the third largest decrease behind only Atlanta and Detroit.

As a result of this white and, to a lesser extent, Chinese resistance to the desegregation plan, Black families in Bayview/Hunters Point also become increasingly frustrated as it became clear that Horseshoe would function as a one-way busing system, taking their children to schools outside of their neighborhood without students from other racial groups being bused into the Bayview schools.

Educational Redesign (1978–1983)

The Plan

In response to white flight and community resistance SFUSD proposed a new student assignment plan, called “Educational Redesign.” The new plan changed the definition of desegregation, abandoning the racial balance requirement in favor of “racial unidentifiability” in each school. This new standard required every school to enroll students from at least four racial/ethnic groups, with no one group exceeding 45% of total enrollment.

In this new plan, family choice was maintained, but the TAP program was replaced by the “Optional Enrollment Request” (OER). The District’s policy was to approve all OERs, as long as the receiving school had space, and the racial unidentifiability of both the sending and receiving schools was maintained.

The Results

Middle-class white and Asian families from neighborhoods on the west side of the city expressed strong support for the new plan, in part as a way to keep their children from being required to attend school outside of their neighborhoods. The Horseshoe Plan had dictated that every student in San Francisco be bused during their elementary school career, but Educational Redesign only required busing in neighborhoods that were not “naturally integrated.” In practice, this meant that middle class largely white and Asian students on the west side of the city could attend a school in their “naturally integrated” neighborhood while lower income Black, Latinx, and Asian students on the east side of the city were more likely to be assigned a school outside of their neighborhood.

Black students were disproportionately assigned to be bused compared to every other racial group in the district. This unequal and unfair distribution of the burden of desegregation frustrated many Black families, especially from Bayview/Hunters Point. In 1983, Black families in Bayview/Hunters Point led weeks of protests against the unfair one-way busing burden placed on their children. Interviews from that period show that protesters were not against busing entirely, but simply wanted the burden to be shared equally among all San Francisco families.

The San Francisco branch of the NAACP sued SFUSD over Educational Redesign, arguing that it would have a segregating effect on San Francisco’s schools. The OER system that families could use to opt out of desegregation was also a major concern for the NAACP and other desegregation advocates.

Optional Enrollment Request (OER) Student Assignment System (1983–2000)

The Plan

In 1983, the NAACP and SFUSD entered into a court-approved desegregation consent decree, which had two primary goals for SFUSD:

- continued and accelerated efforts to achieve academic excellence for all students with a particular focus on African American and Latino students; and

- elimination of racial/ethnic segregation or identifiability in any school, program, or classroom to the extent practicable.

In implementing the 1983 Consent Decree, SFUSD created a student assignment plan and a transportation system designed to support SFUSD’s efforts to desegregate its schools. The student assignment plan used a combination of schools with both contiguous and noncontiguous attendance areas, alternative schools (without attendance areas), and optional enrollment requests which allowed students to transfer to schools outside of their attendance area school. Using Educational Redesign’s racial unidentifiability standard of desegregation, no school could have fewer than four racial/ethnic groups, and no racial/ethnic group could constitute more than 45% of the students at attendance area schools or 40% at alternative schools.

The plan also called for increased resources for schools in the Bayview/Hunters Point, both to address historical neglect and in an attempt to attract families from outside the neighborhood.

The Results

The first decade of the desegregation plan successfully reduced racial identifiability in SFUSD; in 1992, the District reached a low of only one racially identifiable school in the entire district. Though the consent decree was quite successful at reducing segregation, especially at the school level, within-school segregation due to academic tracking remained a big issue.

However, the OER system always threatened to disrupt the desegregation plan, and in the 1990s, it did just that. As OERs increased in the 90s, so did segregation: by 1998, there were thirty-four segregated schools, up from just one in 1992. In 1991, almost 40% of SFUSD students went to school on an optional enrollment permit; by 1999, that number had climbed to 56%.

In addition to the troubling resegregation that began in the 90s, there were also concerns that schools were desegregated on paper, but not in reality, because families could misreport their child’s race/ethnicity to gain admission to their preferred school.

The Courts Forbid the Use of Race in Student Assignment (1999)

As San Francisco’s demographics changed throughout the 80s and 90s, so too did the effects of the desegregation consent decree. In particular, as our Chinese American student population grew, they became the student group most affected by the consent decree’s enrollment requirements, often being assigned to schools outside their neighborhoods in order to maintain racial unidentifiability.

In 1994, the Chinese American Democratic Club found a group of Chinese American parents to sue the District for using race as a factor in school assignment, and as part of a 1999 court settlement, SFUSD was prohibited from using race or ethnicity as a consideration in student assignment. As a result, the 1998–99 school year was the last year that race was used to assign students to schools.

Many opponents of this race-blind settlement plan, including Chinese for Affirmative Action (CAA), feared that it would accelerate the resegregation of San Francisco’s schools — a fear that has been realized over the past two decades. Furthermore, CAA worried that the settlement would create the perception that the Chinese American community of San Francisco was opposed to integration, even though groups like CAA represented many Chinese American families who supported the use of race in student assignment.

The settlement meant that SFUSD had to devise a new student assignment plan that did not include race as a factor. From 1999–2001, the District assigned students using a “default” system, assigning students to schools based on attendance zones, and continuing to accept OERs, with racial caps no longer enforced. For the 2001–02 school year, while SFUSD was working to develop a new court approved student assignment method, students were assigned to schools using a randomized computer lottery that did not consider race or any other demographic factors, and attempted to assign students to a highly ranked choice.

Diversity Index Lottery (2002–2010)

The Plan

In 2002, the District created a new, race-neutral, assignment plan called the Diversity Index Lottery. Since racial diversity was still a major goal, but the District could no longer use race in student assignment, SFUSD turned to multiple race-neutral factors — things like mother’s education level, student socioeconomic status, test scores, English proficiency — that would ideally lead to racially and ethnically diverse schools.

For 9 years, from 2002 through 2010, students were assigned to schools using this plan that was approved by the Courts as part of the desegregation Consent Decree. The process was designed to give parents choice, ensure equitable access, and promote diversity without using race/ethnicity. Families could list up to seven choices on their application form, and students would get assigned to schools via a formula that considered race neutral factors and calculated the probability that, in a given grade, randomly chosen students would be different from each other. All of the race neutral factors were correlated with academic achievement.

The Results

The Diversity Index Lottery was limited in its ability to create diverse schools because the applicant pools for individual schools were racially isolated. In addition, participation in the choice process varied by race/ethnicity — white and Asian families were much more likely than African American and Latinx families to submit their choices in January for August enrollment. As a result, all the high demand schools were full when many African American and Latinx families applied, limiting their choices to underenrolled schools. The court-appointed desegregation monitor urged the District to increase its outreach efforts in the African American and Latinx communities. Over the years, we’ve consistently heard from the community that not all families have the same opportunity to go on school tours in the middle of the work day, and many families prefer to make decisions about school enrollment closer to the start of the school year. This unequal access to school choice systems remains an issue in SFUSD to this day.

On December 31, 2005, the courts allowed the consent decree to expire, and for the first time in 22 years the courts did not oversee SFUSD’s student assignment process.

In 2008, the Board of Education launched a process to develop a new student assignment system because the diversity index lottery was not reducing racial isolation and it was complicated and difficult to understand. The number of schools with high concentrations of a single racial/ethnic group increased over the years under the diversity index. In 2008, a quarter of SFUSD’s schools had more than 60% of a single racial/ethnic group, even though SFUSD’s overall enrollment was racially/ethnically diverse and did not have a majority group.

Current Student Assignment System (2011-present)

The Plan

In March 2010, the Board of Education approved our current student assignment policy, which was designed to use a full choice system — in which families could apply to any school in the District — to overcome residential segregation. The Board’s priorities for a new system were to reverse the trend of racial isolation and the concentration of underserved students in the same school; provide equitable access to the range of opportunities offered to students; and provide transparency at every stage of the process. Unlike the Diversity Index Lottery, which asked applicants to self-report a list of race-neutral factors and caused concerns that some applicants were “gaming” the system by misreporting characteristics, now families only need to share their home address and which schools they wish to attend.

SFUSD also revised attendance area boundaries (many of which had not been altered in decades), developed a Middle School Feeder system, created a preference for students living in the areas of the city with the lowest average test scores (CTIP1), and differentiated the process for elementary, middle, and high school applications.

Families can rank any number of schools on their application, and, if there are no space limitations, students are assigned to their highest ranked choice. If more students request a particular school than there are seats available, assignments are made using a series of preferences, called tiebreakers, and random numbers to assign students to schools. Tiebreakers for elementary schools include:

- Younger siblings of students who are currently enrolled in and will be attending the school

- PreK or TK students who live in the attendance area of the school they’ve requested and are enrolled in an SFUSD PreK or TK in that same attendance area

- Students who live in the areas of the city with the lowest average test scores

- Students who live in the attendance area of the elementary school requested (some elementary schools with unique programs, like language pathways or K-8 schools, do not have attendance areas and do not provide a tiebreaker to students who live nearby.)

The Results

Despite the current plan’s theory that more choice would result in more integration, the opposite has turned out to be true. As the court-appointed desegregation monitor pointed out during the Diversity Index era, access to choice remains unequal under the current system. Since the choice process requires time to “shop” for schools by attending open houses during work hours, knowledge of the application system and paperwork, and transportation access to make crosstown schools viable options, it has turned out that more affluent families are much more likely to participate in the choice process. Despite the District’s good intentions, San Francisco’s schools are more segregated now under the current policy than they were thirty years ago. In 2019, nearly 60% of SFUSD’s elementary schools enrolled more than 45% of a single racial/ethnic group, and a quarter enrolled more than 60% of a single group, even though SFUSD’s overall population was racially/ethnically diverse with no group constituting more than 30% of total K-5 enrollment.

In 2018, the school board voted unanimously to create a new plan to address this troubling segregation, and to make the process more predictable, simple, and transparent for all families. We are currently in the middle of this planning process.

Conclusion

Although San Francisco has come a long way from the legal and de-facto segregation that occurred before 1971, our more recent student assignment plans have never sustained integrated schools, and over the past three decades, segregation has risen in SFUSD. It is important to understand the white supremacist history of residential and school segregation in San Francisco (for a reminder on this history, read Part I of this post), and to learn from the successes — and setbacks — of SFUSD’s more recent attempts to integrate our schools.

Over the past 50 years, SFUSD has maintained a goal to eliminate segregation and deliver an excellent education for every student. But despite our best intentions, our current plan has not worked. Today, we have a unique opportunity to take decisive action to reverse the troubling resegregation of our city’s schools, and ensure equitable educational access for children of all backgrounds. If you are interested in learning more or being involved in this exciting process, please visit sfusd.edu/studentassignment.

This is the third of five posts in SFUSD’s Student Assignment Blog.

The Student Assignment Blog is written and edited by Reed Levitt (SFUSD Communications Intern & Master of Public Policy Candidate, Goldman School of Public Policy at UC Berkeley) and Henry O’Connell (Student Assignment Project Manager, SFUSD).

If you are interested in learning more about the history of San Francisco’s student assignment policies, please check out Rand Quinn’s Class Action: Desegregation and Diversity in San Francisco Schools, the comprehensive book that formed the backbone of this post. Other sources are hyperlinked throughout the post.

This page was last updated on July 26, 2021